Deutsche Version unterhalb des englischen Texts

The main plant of absinthe – the great wormwood – has been known as a medicinal plant for thousands of years.

The origins of the Absinthe as a drink are not exactly proven and probably go back to Henriette Henriod called “Mère Henriod”, who lived in Couvet in the Val-de-Travers in the middle of the 18th century.

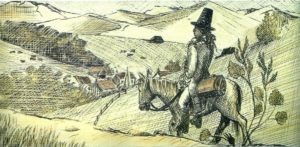

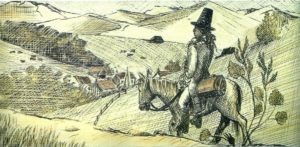

Her Absinthe was distributed by a Dr. Ordinaire, who rode on his small Corsican horse through Canton Neuchâtel and sold Absinthe as a elixir against many common health issues.

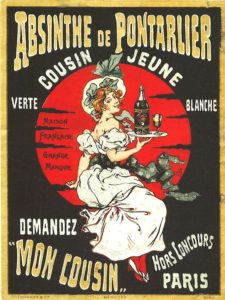

Towards the end of the 18th century, Major Dubied discovered that Absinthe had potential not only as a medicine but also as a drink and bought the recipe from Mère Henriod. Since he knew nothing about distilling, he joined forces with the son of a distiller and founded the first Absinthe distillery with Henri-Louis Pernod in Couvet in 1798. In 1804 Henri-Louis Pernod founded another distillery in Pontarlier to meet the demand in France and to save customs.

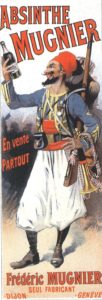

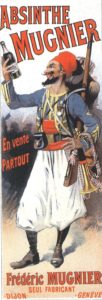

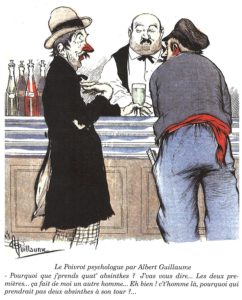

In the next decades Absinthe remained a regional liqueur made from the three basic ingredients wormwood, anise and fennel as well as various other herbs. This changed with the Algerian War in 1830, when Absinthe was given to French soldiers to prevent malaria and dysentery. The soldiers liked this and very soon daily prophylaxis in the form of “heure verte” became established.

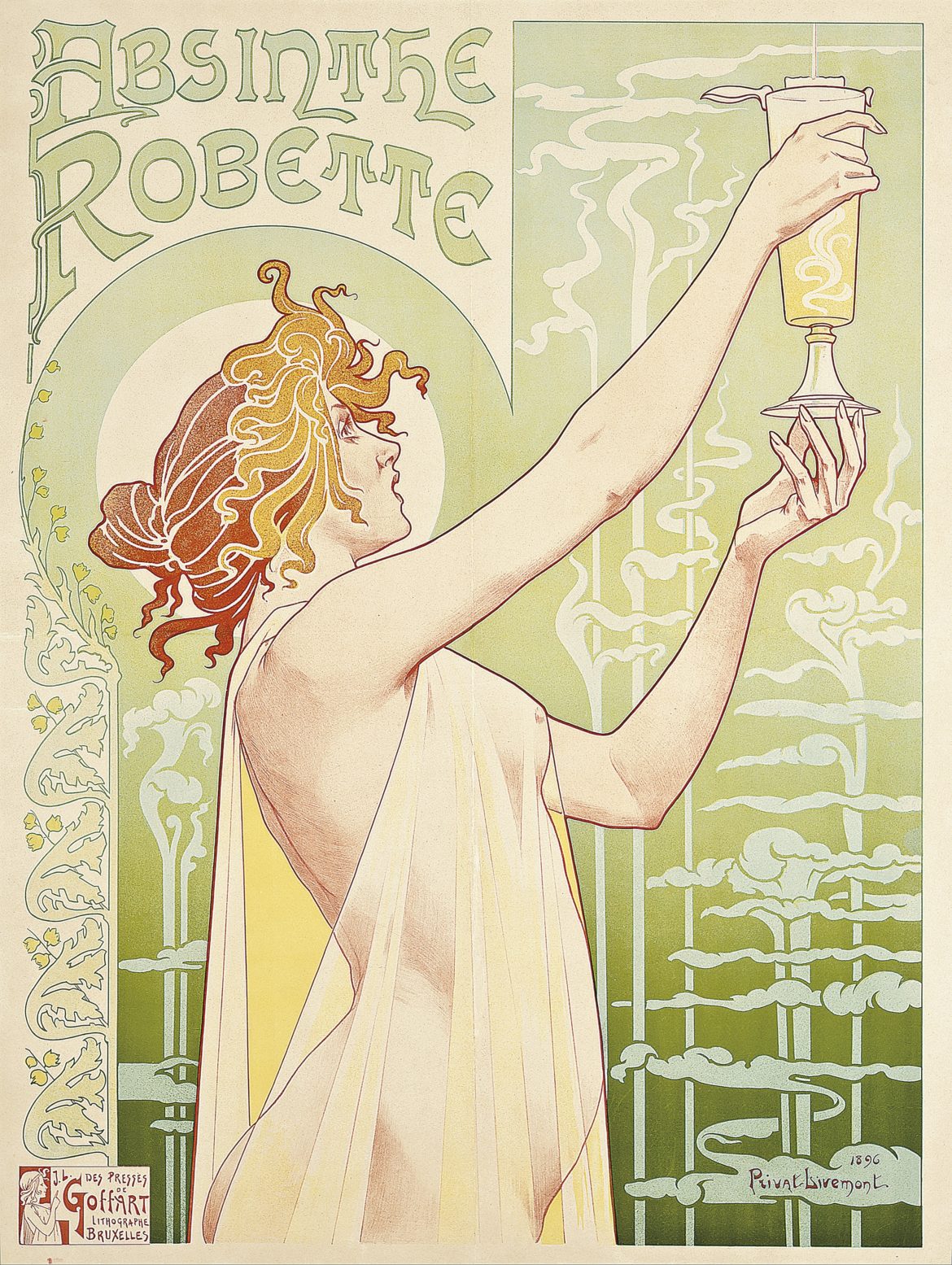

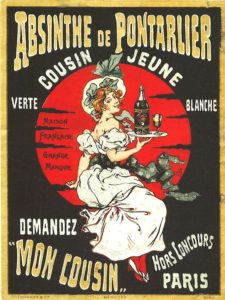

The returning soldiers brought this tradition back to France and soon the „heure verte“ was also celebrated in the Grands Cafés along the big boulevards in Paris. Absinthe became a fashionable drink for bohemians and artists and experienced a massive boom. Arund 1900 there were over 200 distilleries in France, 25 of which were in the Pontarlier area. There were also around 40 distilleries in Switzerland, 13 of them in Val-de-Travers.

At the end of the 19th century, the phylloxera plague invaded Europe’s vineyards and destroyed 2/3 of Europe’s entire vine stock. In France, wine production around 1880 was under a quarter of that of a few decades earlier.

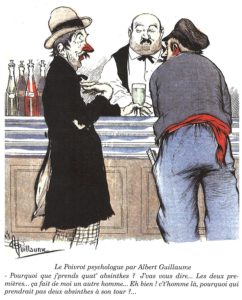

As a result, wine became more expensive and absinthe cheaper, as the latter was no longer produced with wine alcohol but cheaper alcohol. Absinthe changed from a fashionable drink to a mass drink and replaced wine in this regard. Parallel to this, industrialisation took place in the middle of the 19th century and a new working class emerged, which “fought” the often poor working conditions with alcohol. At the end of the 19th century alcoholism therefore became a social problem, which led amongst others also to the foundation of the Blue Cross around 1885.

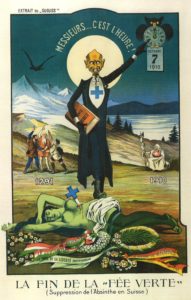

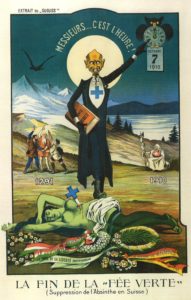

At the beginning of the 20th century it was an unholy alliance of abstinence advocates and winegrowers – who promoted wine as a natural product in contrast to the artificially produced Absinthe – who fought together against the Absinthe.

In 1905, an incident occurred in the canton of Vaud that broke the camel’s back: an unemployed farm worker named Jean Lanfray killed his pregnant wife and his two little daughters. Lanfray was a strong alcoholic and drank between 2 and 5 litres of wine a day. But before he did the murder, he had also drunk two glasses of Absinthe, whereupon the Absinthe opponents rushed and exploited this fact in the media. Belgium banned Absinthe in 1905. In Switzerland this was put into force by referendum in 1910. In France, the ban came into force in 1914. In other countries, such as Spain, England or Portugal, the production and sale of absinthe remained legal.

In the 19th century Absinthe was considered an addiction in its own right, alongside alcoholism. However, scientific studies of pre-ban Absinthe bottles carried out at the end of the 20th century showed that their thujon content was far too low to cause health problems or the hallucinations attributed to the Absinthe. The practical reason for this is the bitterness of the wormwood, which is why it – and therefore the thujone – can only be contained in the Absinthe in limited quantities. The negative consequences of Absinthe consumption were therefore primarily the consequences of excessive alcohol consumption and not any Absinthe-specific ingredients.

The lifting of the Absinthe ban is largely due to the EU. According to the “Cassis de Dijon Principle”, a product manufactured in one EU country can also be sold without further restrictions in the rest of the EU. Since the production and sale of Absinthe was legal in Spain, Portugal and England, the European Court of Justice ruled in 1979 that this was legal in the other EU countries as well. However the respective laws were only modified in France in 1999 and in Switzerland in 2005. The latter in connection with the complete revision of the Federal Constitution.

The handling of the Absinthe ban was quite different in France and Switzerland. In France, no absinthe was produced during the ban and distilleries produced alternative products such as Pastis. Pastis was not allowed to contain wormwood, had to contain a minimum amount of sugar and had the alcohol concentration was restricted.

In Switzerland, on the other hand, Absinthe was burned black during the entire prohibition period. The estimated annual production was approximately 15,000 litres. The Federal Administration even supplied the distillers with the necessary alcohol and the occasional fines were moderate. In French-speaking Switzerland, it was almost a good habit for judges and government officials to occasionally drink an Absinthe.

For the classic drinking ritual it is best to use a so-called Pontarlier glass, in which approximately 2-3 cl Absinthe and then up to the second mark approximately 1 dl water is poured. This turns a 60% Absinthe into a drink with 5-8 percent Alcohol, corresponding to a beer or a light wine. In the traditional preparation, the ice-cold water from the Absinthe Fountain drips onto a piece of sugar lying on a perforated spoon on the glass.

There are two main types of Absinthe. The clear distillate is called “blanche” in France and “bleue” in Switzerland. The green Absinthes called “vertes” are macerated again with hashed and dried herbs after distillation.

Sources:

Delahaye Marie-Claude, L’Absinthe – Son Histoire, 2001

Kaeslin Jacques / Michael district, L’absinthe au Val-de-Travers. Les origines et les inconnu(e)s, 2011

Nathan-Maister David, The Absinthe Encyclopedia, 2009

***

Kleine Einführung in den Absinthe

Die Hauptpflanze des Absinthes – der grosse Wermut – ist seit Jahrtausenden als Heilpflanze bekannt.

Die Ursprünge des Absinthes als Getränk sind nicht exakt belegt und gehen wahrscheinlich zurück auf Henriette Henriod genannt „Mère Henriod“ welche Mitte des 18. Jahrhunderts in Couvet im Val- de- Travers lebte.

Ihr Absinthe wurde u.a. von einem Dr. Ordinaire vertrieben, der auf seinem kleinen korsischen Pferd durch den Kanton Neuenburg ritt und dieses als Allheilmittel gegen Frauenbeschwerden und sonstige Zipperlein verkaufte.

Gegen Ende des 18 Jahrhunderts entdeckte ein Major Dubied, dass der Absinthe nicht nur als Medizin sondern auch als Genussmittel Potenzial hat und kaufte Mère Henriod das Rezept ab. Da er nichts vom Brennen verstand, tat er sich mit dem Sohn eines Destilleurs zusammen und gründete zusammen mit Henri-Louis Pernod im Jahre 1798 in Couvet die erste Absinthe Brennerei. Um die Nachfrage in Frankreich zu decken und um Zoll zu sparen, gründete Henri-Louis Pernod im Jahre 1804 eine weitere Brennerei in Pontarlier.

In den nächsten Jahrzehnten blieb Absinthe ein regionaler Kräuterlikör aus den drei Grundzutaten Wermut, Anis und Fenchel sowie diversen weiteren Kräutern. Dies änderte sich mit dem Algerienkrieg ab 1830: dort wurde Absinthe den französischen Soldaten verabreicht zur Prävention von Malaria und Ruhr. Den Soldaten schmeckte dies und sehr bald etablierte sich die tägliche Prophylaxe in Form der „heure verte“.

Die Kriegsrückkehrer brachten diese Tradition zurück nach Frankreich, insbesondere nach Paris und bald wurde die heure verte auch entlang der grossen Boulevards zelebriert. Absinthe wurde zum Modegetränk der Bohemiens und Künstler und erlebte einen massiven Aufschwung. Es gab in Frankeich über 200 Destillerien, davon über 25 in der Umgebung von Pontarlier. In der Schweiz gab es ebenfalls rund 40 Destillerien, 13 davon im Val- de- Travers.

Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts befiel die Reblausplage die Weinberge Europas und vernichtete 2/3 des gesamten Rebbestands Europas. In Frankreich betrug die Weinproduktion um 1880 noch knapp ein Viertel verglichen mit ein paar Jahrzehnten zuvor.

Dies hatte zur Folge, dass Wein teurer wurde und der Absinthe günstiger, da dieser nicht mehr mit Weinalkohol sondern billigerem Alkohol hergestellt wurde. Absinthe wurde vom Modegetränk zum Massengetränk und löste diesbezüglich den Wein ab. Parallel dazu fand in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts die Industrialisierung statt und eine neue Arbeiterklasse entstand, welche die oft schlechten Arbeitsverhältnisse mit Alkohol „bekämpfte“. Ende des 19 Jahrhunderts wurde deshalb der Alkoholismus zu einem gesellschaftlichen Problem, welcher etwa 1885 zur Gründung des Blauen Kreuzes führte.

Anfangs des 20. Jahrhunderts war es eine unheilige Allianz aus Abstinenzverfechtern und Weinbauern – welche den Wein als Naturprodukt im Gegensatz zum künstlich hergestellten Absinthe anpriesen – die gemeinsam gegen den Absinthe kämpften.

Im Jahre 1905 geschah ein Vorfall im Kanton Waadt, welcher das Fass zum Überlaufen brachte: Ein arbeitsloser Landarbeiter namens Jean Lanfray brachte im Rausch seine schwangere Frau und seine zwei kleinen Töchter um. Dieser war starker Alkoholiker und trank täglich zwischen 2 und 5 Liter Wein. Vor der Tat hatte er aber auch zwei Gläser Absinthe getrunken, worauf sich die Absinthe Gegner stürzten und diese Tatsache medial ausschlachteten. Belgien erliess noch 1905 ein Absinthe Verbot. In der Schweiz wurde dieses via Volksabstimmung per 1910 in Kraft gesetzt. In Frankreich trat das Verbot 1914 in Kraft. In anderen Ländern wie z.B. Spanien, England oder Portugal blieb Absinthe erlaubt.

Im Jahre 1905 geschah ein Vorfall im Kanton Waadt, welcher das Fass zum Überlaufen brachte: Ein arbeitsloser Landarbeiter namens Jean Lanfray brachte im Rausch seine schwangere Frau und seine zwei kleinen Töchter um. Dieser war starker Alkoholiker und trank täglich zwischen 2 und 5 Liter Wein. Vor der Tat hatte er aber auch zwei Gläser Absinthe getrunken, worauf sich die Absinthe Gegner stürzten und diese Tatsache medial ausschlachteten. Belgien erliess noch 1905 ein Absinthe Verbot. In der Schweiz wurde dieses via Volksabstimmung per 1910 in Kraft gesetzt. In Frankreich trat das Verbot 1914 in Kraft. In anderen Ländern wie z.B. Spanien, England oder Portugal blieb Absinthe erlaubt.

Im 19. Jahrhundert wurde der Absinthismus als eigenständige Sucht neben dem Alkoholismus betrachtet. Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts durchgeführte wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen von pre-ban Absinthe Flaschen haben jedoch ergeben, dass deren Thujon Gehalt bei weitem zu niedrig war, um gesundheitliche Beeinträchtigungen oder die dem Absinthe zugeschriebenen Halluzinationen auszulösen. Der praktische Grund dafür ist die Bitterkeit des Wermuts, weshalb er und somit das Thujon nur in begrenzten Mengen im Absinthe enthalten sein können. Die festgestellten negativen Folgen des Absinthe Konsums waren somit in erster Linie die Folgen des übermässigen Alkoholkonsums und nicht irgendwelcher Absinthe-spezifischer Inhaltsstoffe.

Die Aufhebung des Absinthe Verbots ist im Wesentlichen der EU zu verdanken. Gemäss dem „Cassis de Dijon Prinzips“ kann ein Produkt, welches in einem EU Land gesetzeskonform hergestellt wurde, auch in der übrigen EU verkauft werden. Da Herstellung und Verkauf von Absinthe in Spanien, Portugal und England legal waren, war dies nach einem Urteil des Europäischen Gerichtshofs bereits ab 1979 wieder möglich. Die Gesetze wurden aber in Frankreich erst 1999 und in der Schweiz gar erst 2005 – im Zusammenhang mit der Totalrevision der Bundesverfassung – angepasst.

Der Umgang mit dem Absintheverbot war in Frankreich und der Schweiz ziemlich unterschiedlich. In Frankreich wurde während des Verbots keinerlei Absinthe produziert und Destillerien haben alternative Produkte wie etwa Pastis hergestellt. Dieser durfte keinen Wermut enthalten, musste eine Mindestmenge Zucker beinhalten sowie einen maximalen Alkoholgehalt aufweisen.

In der Schweiz hingegen wurde während der ganzen Prohibitionszeit schwarz gebrannt. Die geschätzte Jahresproduktion umfasste circa 15‘000 Liter. Die Bundesverwaltung belieferte die Brenner mit dem notwendigen Alkohol, die gelegentlich verhängten Bussen waren moderat und es gehörte in der Westschweiz für Richter und Regierungsräte fast zum guten Ton gelegentlich einen Absinthe zu trinken.

Für das klassische Trinkritual verwendet man am besten ein sogenanntes Pontarlier-Glas, in welchem man bis zur ersten Markierung circa 2-3 cl Absinthe und dann bis zur zweiten Markierung circa 1 dl Wasser eingiesst. Damit wird aus einem 60% Absinthe ein Getränk mit 5-8 Prozent Alkohol. Bei der traditionellen Zubereitung tröpfelt das eisgekühlte Wasser aus dem Absinthebrunnen auf ein Stückchen Zucker, welches auf einem gelochten Löffel auf dem Glas liegt.

Man unterscheidet im Wesentlichen zwei Sorten von Absinthe. Das klare Destillat wird in Frankreich „blanche“ und in der Schweiz „bleue“ genannt. Die grünen Absinthes „vertes“, werden nach der Destillation nochmals mit eingelegten Kräutern maceriert.

Quellen:

Delahaye Marie-Claude, L’Absinthe Son Histoire, 2001

Kaeslin Jacques / Kreis Michael, L’absinthe au Val-de-Travers. Les origines et les inconnu(e)s, 2011

Nathan-Maister David, The Absinthe Encyclopedia, 2009